No, the thought didn’t cross her mind.

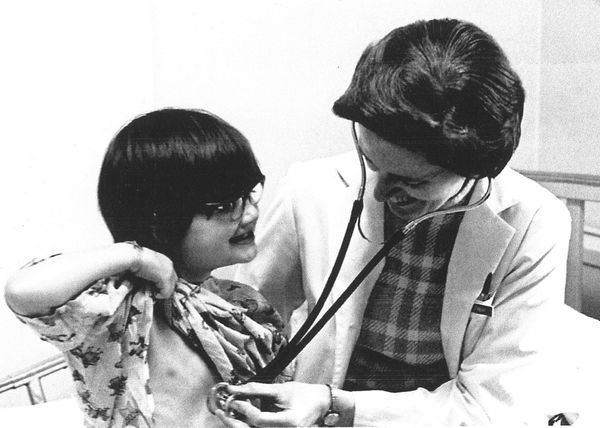

Despite her 85 years, Sr. Katherine Seibert, M.D., ’67 M.S., ’73 PhD continues to practice medicine. An oncologist and internal medicine practitioner, Dr. Seibert — until recently — spent two days a week at Hudson River HealthCare in New York’s Hudson River Valley, an area now regarded as the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

She knew the risks. Demographically, Seibert is among the group most susceptible to the worst effects of the novel coronavirus, with patients 65 and older accounting for nearly three-quarters of hospitalizations in the United States, according to a report released April 9, 2020, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That’s what her other training — as a Sister of Charity — has prepared her for.

“Even at 85, I’m not going to walk away and say I’m high-risk,” Seibert said. “I don’t think that’s what God wants me to do.”

Now, however, with the region hitting its peak, Seibert has been forced home as her HRHCare office has closed and consolidated with a nearby office to treat coronavirus patients. Seibert continues to see patients via telemedicine, but it took a directive for her to reach that point.

After taking her vows in 1954, Seibert taught as a young nun. In the 1960s, Notre Dame offered a teacher training program, which she attended in the summers and, after five years, earned her master’s in biology in 1967. After graduation, Rev. James Doll, C.S.C. ’42, who Seibert had met through their work at Notre Dame’s LOBUND Laboratories, had asked her to stay, but it wasn’t until the fall of 1968 when she returned to pursue a doctorate in microbiology.

During her nights in Lewis Hall, Seibert struggled to sleep as her thoughts were occupied by people struggling with cancer. She knew she could serve those people more effectively in the medical field, so just before completing her PhD, she approached her superior about attending medical school. Three years later, she graduated from Creighton with intentions to pursue oncology.

Following medical school, she trained at the National Cancer Institute and St. Jude’s Hospital in Memphis. After serving as chief of medical oncology at several hospitals in New York City, she was recruited to develop an oncology program in Sullivan County, New York, where there had been no cancer services previously. She also spent time in Billings County, North Dakota, setting up an oncology program there.

Ultimately, she moved to internal medicine when her sister became ill and has served as an internist at Hudson River HealthCare since 2007. Founded in the early 1970s by four women in the basement of a church to address the lack of accessible and affordable health care services in Peekskill, New York, HRHCare now serves 10 counties in the Hudson Valley and Long Island and treats not only the insured, but the uninsured and undocumented, regardless of their ability to pay.

“As a Sister of Charity, in our tradition, we have a bias to the poor,” Seibert said. “We use the rule of Vincent De Paul (which places an emphasis on a vocation of helping the needy), so if you have to make a choice, you would always have a bias towards the poor. And, surely, for the most needy, anything you can do is a help.”

In a culmination of her work, Seibert was presented with the Notre Dame Alumni Association’s Thomas A. Dooley Award, conferred on alumni who have exhibited outstanding service to humankind, in 2018.

Before her office closed, Seibert and her colleagues were seeing a number of coronavirus patients, donning full protective gear to meet them in the parking lot of the clinic to administer the test. While many were young and asymptomatic, they were often poor and could not afford to stay away from work.

At the time, the idea she would hold herself back for fear of infection was far from her mind. She thought of that line from The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.” The most valuable things in life cannot be seen, only felt.

“Tomorrow I’m going to the office knowing that the virus can kill me,” she said then, “but I’m seeing rightly. You see the need and you do it.”

She is quick to point out that the “real heroes” are the health care workers in hospitals, particularly in areas like New York that are facing shortages of everything from personal protective equipment to ventilators to ICU beds.

“The real heroes are in the hospital on the front lines, and it’s scary,” Seibert said. “They’re putting people on ventilators, no visitors, even if you’re dying.

“In New York, if you have the virus (as a health care worker), you can be out of work for seven days, and then if you have no fever for three days, you go back. That’s how shorthanded they are. They’re the real heroic ones.”

If her history is any indication, however, it’s clear Seibert would prefer to be back in her practice, as telemedicine visits aren’t quite the same for someone with an “old-school” approach. She’s guided by Matthew 10:8, which says, “Heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse the lepers, cast out demons; freely you received, freely give.”

“I felt it was more or less a call from God (to practice medicine),” Seibert said. “If God gives you a gift, give it back as a gift. You spend your whole life harvesting this gift … and when you give something as a gift, you give it with a certain attitude, not grudgingly. Even now, it’s tough to practice medicine like this, but you do the best you can."

Chris Palmquist '13 contributed to this story.