In the decades he’s worked to help people with developmental disabilities, Kevin Urtz ’77 has learned the importance of overcoming fear.

There’s the fear families face when they think about a child’s future. The fear a client experiences when they consider the challenges ahead. And the fear others may feel in dealing with difference.

“If there’s anything I can say, it’s that you’ve got to reduce fear in people,” Urtz says. “Everyone has a disability of one kind or another, and fear is probably the worst one.”

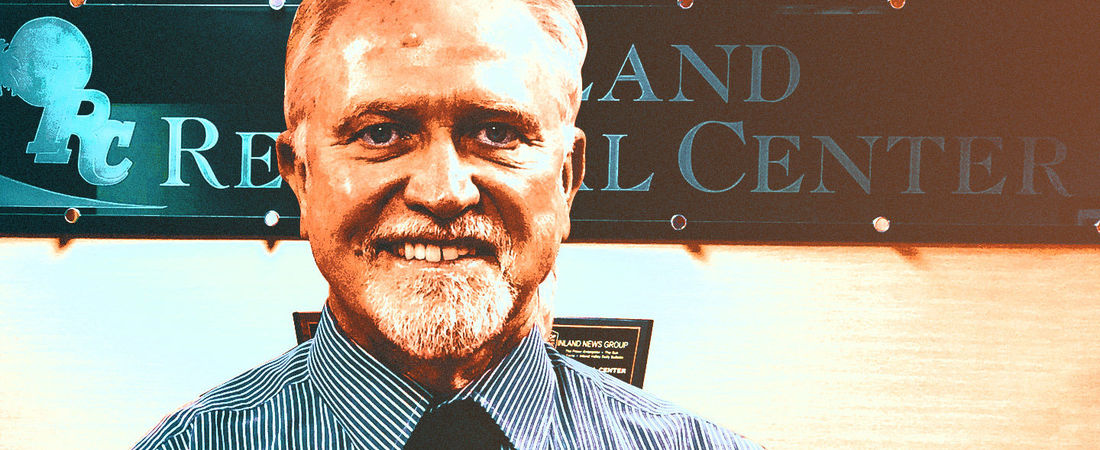

And Urtz has helped people overcome fear in his work with Inland Regional Center. The nonprofit, which is the largest of California’s 21 regional centers for people with developmental disabilities, serves almost 39,000 clients in the Inland Empire, a sprawling area in the southern part of the state that is home to roughly 4.5 million people in Riverside and San Bernardino counties. Urtz, who joined the organization in 1990, has been its associate executive director since 2015.

Improving Quality of Life

Over his career, Urtz has worked to help clients become as independent as possible, and has seen good results.

“When I started, most of our clients were in segregated settings—day program settings or residential settings, if not institutionalized,” he says. “And now, it’s much more individualized. The focus is on community involvement and inclusion. Over the years, the community has become more acclimated to seeing our clients. And they’re more comfortable, and so our clients are more comfortable. And a lot of that fear our clients had or that the community had of them has gone away.”

Inland serves a range of people with intellectual disabilities, autism, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy, Urtz says. In California, people with developmental disabilities are legally entitled to a variety of services, and the nonprofit has a contract with the state to help meet a growing demand. Each year, he says, it takes on another 2,000 clients.

“We see them at least once a year, and more if needed,” Urtz says. “And the goal is to set up an individual program plan to help them accomplish what they hope to do over the next year. And because there’s such a range of degree of disability and type of disability, they are pretty individualized. Our underlying mission is to help people be as independent as possible.”

To accomplish that, Inland’s case managers connect clients with existing mental health, education, and social services. But the agency also supplements this by developing and funding other services as needed. This can include advocacy, behavior modification, and supportive living services—helping clients with budgeting, cooking, and transportation—as well as respite care that assists families who are caring for a loved one.

Inland also helps clients find work—something Urtz says is crucial to their ability to become more independent and succeed.

“Our clients are pretty dependable when they’re given an opportunity to really do something,” he says. “Because some of them are succeeding, they’re making a path for other clients down the line. And where that pays off is that it lessens the anxiety in the parents of our younger kids. A big part of this is getting our parents to buy into letting their kids live as normal a life as possible. And there is some dignity of risk for our clients.They have to know that they’ve succeeded themselves, not that you’ve succeeded for them.”

Though he initially planned to be a doctor, Urtz says that in looking back, he realizes he was meant to work with people with developmental disabilities. As a freshman at Notre Dame, he first planned to study pre-med, before chemistry courses got the better of him. But during his first year, he volunteered with Logan Center in South Bend. It was his first real encounter with people who had developmental disabilities, and at the time, he didn’t realize it would be the first of many.

Urtz went on to major in psychology, and later landed a job at a psychiatric hospital in Southern California. When a colleague opened a facility for people with developmental disabilities, Urtz joined him. Almost 30 years ago, he joined Inland Regional Center as a case manager, then worked his way up to program manager.

Challenges and Progress

Inland has faced significant challenges, Urtz says. In 2010, the agency was put on probation after a state audit found it had a hostile work environment. He was promoted to associate executive director in 2015 as part of a new leadership team charged with cleaning things up. He says he and his executive director, Lavinia Johnson, have worked to increase transparency and help the agency’s staff of 780 build better relationships with clients and the community.

“We’ve been trying really hard to change a negative image we had with the community,” Urtz says. “We’re trying to build on that and handle the growth.”

In December 2015, several months after Urtz was promoted, Inland was the site of the mass San Bernardino shooting that killed 14 people and wounded another 22. As the staff worked to process and recover from the tragedy, Urtz says, Inland became stronger.

“Something like that actually brought us together, he says. “A lot of the negativity and issues that we had here kind of dissolved. Everybody realized how serious this was, and if we’re going to pull through this, we can’t have any of this drama.”

In the last three years, Urtz says, Inland has had clean audits, and in 2017 and 2018 the Southern California News Group recognized it as a top workplace in the Inland Empire.

Now, as he helps to lead the organization forward, Urtz continues to see how his work can make a difference. It’s about pushing away fear, he says, and pushing for progress.

“We’re trying to help some people who are struggling and who appreciate being helped,” he says. “There’s a lot of room for progress, and you can see the progress. You’ve been dealt a situation in life and that situation is not going to go away, but we can help you through it.”