When the six-month dry season begins each year in South Sudan, life quickly becomes a struggle to survive.

People in remote areas of the country spend hours each day walking in 120-degree heat to look for water. They abandon their homes for months at a time, unable to build or maintain the schools, markets, and medical facilities their communities need. And when they do find water, it’s often contaminated with bacteria or parasites that can leave them sick or dead.

That’s the struggle Lynn Malooly ’84 addresses in her role as executive director of Water for South Sudan, a nonprofit dedicated to drilling wells across the country.

“The need is tremendous,” Malooly says. “We try to spread out our work to reach as many people as possible.”

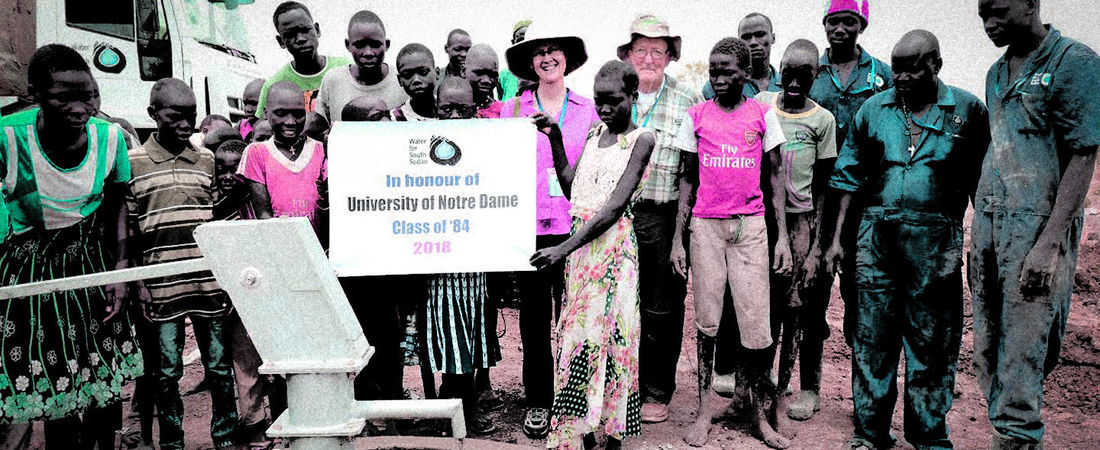

So far, the organization has drilled 340 wells—including one this spring sponsored by Malooly’s classmates—and its goal is to add 40 more each season. Employees work with local officials to determine the best locations for new wells.

“We have our own operations center in South Sudan, so we employ all local people,” Malooly says. “That’s something we’re hugely proud of. We use local, on-the-ground leadership. We want to build our team in South Sudan as much as we want to help villages. The people on our team know the language, the people, the customs, and they can navigate the country in ways that westerners can’t.”

The work doesn’t end when workers finish a well, since each requires periodic maintenance. Last year, Water for South Sudan created a rehab team to fix wells that had suffered cracks or erosion, and the organization has made adjustments to its designs and cement mixes to make wells stronger. It also trains people on sanitation procedures so they can keep their wells and water cans clean.

As more wells emerge across the country, the demand on any one of them decreases, Malooly says. Years ago, a new one might serve anywhere from 3,000 to 5,000 people, but now, the average is more like 600 to 800. This means more people can travel shorter distances to get the water they need to live and work, whether their work is tending to crops or livestock or producing goods. And that transforms their quality of life.

“It’s just incredible,” Malooly says, recalling how better access to water enabled one woman to make two baskets each week instead of one over an entire month—a newfound productivity that gave her enough money to send her daughter to school. “When you hear one story, it really brings home the impact we make.”

Malooly found her opportunity to help make an impact when she discovered the nonprofit several years ago. At the time, it had a small presence in Rochester, New York, where she lived and where its founder, Salva Dut, had settled. Dut was among the approximately 20,000 Lost Boys of Sudan who fled the violence of the country’s civil war in the late 1980s (his story is told in the New York Times bestseller A Long Walk to Water). Malooly, who was looking for a flexible position as she continued to homeschool her youngest child, accepted a part-time administrative job that has since grown into her current leadership role.

“It was a beautiful opportunity for growth, and it worked for me and my family,” Malooly says. “I feel like the luckiest person on earth, and it’s gratifying to be able to help make a difference.”

To learn more about the work Water for South Sudan does to provide clean water, please visit waterforsouthsudan.org.