On the first day of classes each year, public school social studies teacher Zoe (Rote) Kourajian ’16 makes sure her students know “this is not a normal history class.”

“You will not just get a whitewashed perspective of history,” she tells them. “You are going to learn history from tons of different perspectives and learn how to question it.”

Kourajian is currently in her fifth year teaching 8th grade U.S. History at Edgewood Middle School in Mounds View, Minnesota, near St. Paul. There, she challenges her students to confront biases, question societal constructs, and consider how past decisions have led to the present moment. This skills-based approach fosters critical thinking skills and empowers students to become historians, rather than relying on rote memorization to get through her class.

Surprisingly, for much of her life, Kourajian did not enjoy history.

"[I wanted] to be a government teacher," she recalled. "I love the idea of public schools as a breeding ground for democracy. It's where kids learn how to live in community and be positive community members. But then I discovered history taught from a skills perspective instead of memorization. I don't use a textbook. I have two textbooks in my classroom and they're propping up my laptop right now. I don't think textbooks have a place in the modern day history classroom. Once I found that history could be taught [in a different] way, that's when I pivoted from wanting to teach government to wanting to teach history."

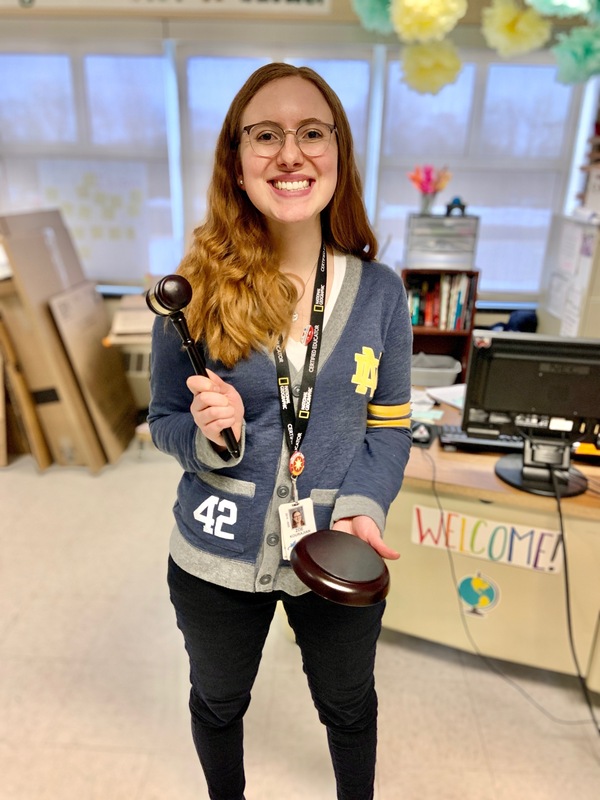

Her innovative approach has made her an educational leader. She is a member of and serves as a mentor in the National Geographic-certified teacher community, and earlier this fall, was named to Notre Dame’s 2021 Domer Dozen cohort. This honor is awarded to 12 young alumni each year who exemplify the core tenets of the Alumni Association’s mission statement — faith, service, learning, and work.

As a Notre Dame student, Kourajian elected to study political science and minored in Education, Schooling, and Society (ESS) in order to pursue her longtime goal of becoming a teacher. She credits the mentorship of ESS professors Dr. Stuart Greene and Dr. Maria McKenna with inspiring her career as a public school teacher.

“[They are] both really big advocates for public education,” she said. “There are a lot of advocates for Catholic education at Notre Dame, but falling under the mentorship of these two people really pushed me to view service to society through the lens of public education. I am really grateful for that.”

Unlike many Domers, Kourajian hadn’t heard of the University until she was a junior in high school. The summer prior to her senior year, she attended a week-long Global Issues Seminar through the Pre-College Leadership Seminars program.

“I had never considered Notre Dame before that. I didn’t know anyone who had attended,” the Greensboro, North Carolina, native said. “Nobody from my high school had gone there before, but I left after that week knowing that’s where I wanted to go to school.”

Once on campus, she pursued many activities that further informed her goals of serving her community and becoming a teacher. In two years as president of Notre Dame’s World Hunger Coalition, she led the club in raising more than $94,000 for hunger-related charities. Additionally, she served as tutor for children at the Robinson Community Learning Center and for Spanish-speaking adults at La Casa de Amistad, and participated in two service-learning seminars through the Center for Social Concerns at Our Lady of the Mountains Catholic School in Appalachia.

In addition to this already extensive list of extracurriculars, Kourajian also logged over 100 hours shadowing teachers in local schools. She said this experience in particular solidified her career goal and granted her the ability to explore that calling.

“I didn’t know exactly what subject I wanted to teach, and I didn’t even know which grade level I wanted to teach,” she recalled. “Having the chance to spend a lot of time with kids in different settings [and] with different age groups helped me find my way to secondary social studies.”

Following her graduation from Notre Dame, she earned a master’s degree in Secondary Social Studies Education from Vanderbilt University’s Peabody School of Education in 2017. Shortly after, she began her current position at Edgewood.

Until this year, Kourajian also taught World Geography. In her time at the school, she has rewritten both that curriculum and the U.S. History curriculum multiple times, making tweaks yearly to reflect our changing world.

“I really aim to make sure that every single one of my students sees themselves reflected in the history that we study,” she said. “I teach at a diverse school with students from tons of different backgrounds, so I want to make sure that they see themselves reflected both in terms of race and ethnicity, but also in terms of religion.”

Her favorite part of teaching this way is that it constantly challenges her to learn more.

“I’m always learning so I can better answer [my students’] questions or understand their communities if I am unfamiliar with them,” she said.

Once, when teaching her students about the Vietnam War, a Hmong student asked Kourajian, “When are you going to start teaching about us?”

The student, a 14-year old, was referring to the Secret War — a covert proxy war orchestrated by the United States but fought in Laos by Hmong soldiers.

Kourajian had never heard of the Secret War, but that night, she researched it and rewrote the following day’s lesson plan to focus on the conflict.

She strives to teach history from what she calls a “perspective of agency.” Rather than simply exposing her students to the injustices that disenfranchised groups have faced, her curriculums encourage students to explore the “why” behind these issues and how similar problems can be prevented.

“These things happened, but let’s question that,” she instructs her students. “Let’s question why they happened. Who was in power when they happened? But also, how did people overcome them?”

This teaching philosophy has created many opportunities for Kourajian’s students to get involved in their local communities, including writing letters to politicians. In one World Geography class, while studying the Amazon Rainforest, her students were inspired to send letters to loggers about their opinions on deforestation.

One of Kourajian’s proudest accomplishments as a teacher is the addition of the National History Day program to Edgewood’s curriculum. National History Day is a nationwide yearly program where over 500,000 students embark on intensive research projects. It fits perfectly with Kourajian’s mission of redefining history from the memorization of facts to a skills-based subject.

“Students work on their projects for 10 weeks and learn how to do primary and secondary source research, how to write a historical thesis, how to back up an argument with evidence, [and] how to create a presentation for an authentic audience,” Kourajian explained.

Now in her third year leading the program, she said National History Day has allowed students from underrepresented groups to research and further explore aspects of their own family and cultural histories.

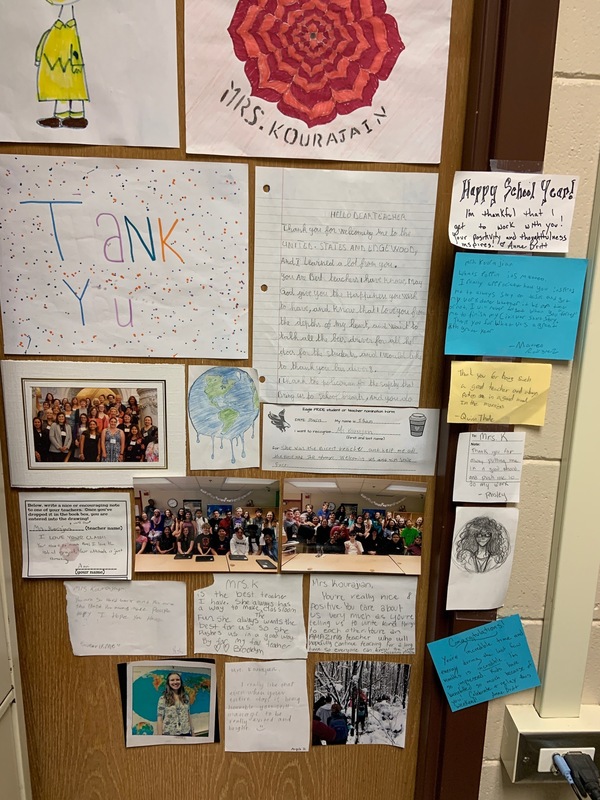

“I had a student last year who’s Native American,” she said. “She wrote me a letter saying that she always hated U.S. History because she was always left out of it. She thought she would hate my class, but after a year in my class, it was her favorite because she finally felt seen. … That one’s hanging up.”

Kourajian shifted her laptop camera to the white cinderblock wall beside her desk in her classroom. It’s covered in letters and drawings — sometimes sent to her two or three years after being in her class — from students who have been inspired by her teaching.

“Those letters mean a lot to me,” she said, emotion rising in her voice. “The day-to-day of teaching is really awesome, but it’s very hard and challenging and I work long hours. It’s a struggle to find a work-life balance, but those letters remind me of what’s being done here.

“I love my students so much, and they know that. I don’t think kids learn from people they don’t like, so my number one thing is relationships with my kids.”

It’s this love she has for her students that’s the reason Kourajian plans to be a public school classroom teacher for the entirety of her career.

“There are certain leadership opportunities where you stay a teacher but then also mentor other teachers that I’m interested in, but I always want to stay in the classroom,” she said. “It’s what I love. I don’t want to be in a position where I’m not surrounded by kids every day and … having a full year of growing with them."