As Scott Buchanan ’79 describes it, Newtown, Connecticut, was an anonymous small town. Then, on December 14, 2012, a young man walked into Sandy Hook Elementary with a gun and killed 20 first-grade students and six educators.

The lives of those 26 families were forever changed. But so too were those of the survivors—students and staff from the school, police officers, emergency responders, funeral home directors, neighbors, and pastors. Everyone in the tight-knit community knew someone impacted, Buchanan says. Overnight, the quiet town of about 27,000 people was thrust into the media spotlight while trying to grieve and understand a horrific and traumatic event.

Hundreds of reporters flooded the town with a need to fill a 24-hour news cycle. Quickly after, hordes of volunteers—some qualified, others less so—overwhelmed the town. And then, as suddenly as they arrived, the strangers disappeared.

“You have this initial influx of all these people who come in, but then they leave,” Buchanan says. “As a community, we have to figure out what to do in the aftermath. And of course, nobody knows. There’s no book on how to deal with a tragedy like that.”

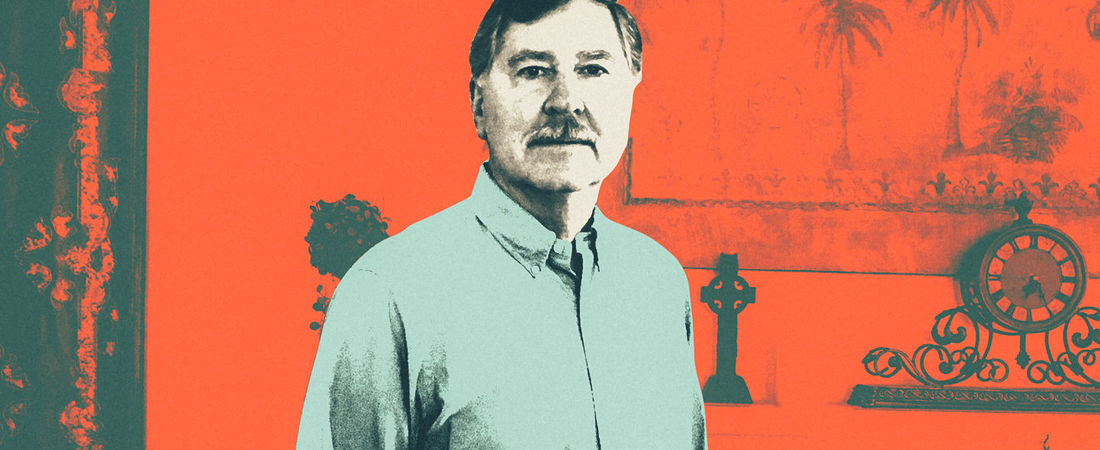

What he did know was the solution had to come from inside the community. Newtown has been Buchanan’s home for more than 26 years. There, he raised his children and led a successful career at PepsiCo, retiring at the end of 2011 as the senior vice president of procurement. So in the wake of the horror at Sandy Hook, he knew he needed to serve his friends and neighbors. When a call came from a former PepsiCo colleague asking for his business expertise as her sister-in-law started up a nonprofit called the Resiliency Center of Newtown, he jumped at the opportunity.

“To me, it was the hand of God that laid this opportunity and said this is what you need to go do,” he says.

The Resiliency Center, the brainchild of founder and executive director Stephanie Cinque, was designed to offer creative therapies and community wellness to anyone struggling with the trauma of the shooting. Notably, the Resiliency Center would focus on alternative therapies, including art, music, and play, in order to best serve the children and families impacted by the tragedy who might not benefit from traditional talk therapy.

“We didn’t want to be a duplicate of what existed. We wanted to put in therapies that would provide different avenues for different people to find ways for healing,” Buchanan says. “We were trying to provide as many opportunities as we could for people to find ways to deal with the tragedy.”

In 2016, a community survey would note that several of the therapies provided exclusively at the Resiliency Center were some of the most effective intervention techniques. The center has also put on summer camps and community events, and has space for people to visit, gather, or work in a safe environment. Buchanan says the center’s leadership was keen to staff it with people from the community who would have a particular sensitivity to the needs of the town.

While Buchanan is quick to note he is no therapist, his business acumen was critical to the success of the center, which still sees more than 500 people each year. His longtime work with the Women’s Business Enterprise National Council in Washington, D.C., provided helpful experience in the launch and maintenance of the Resiliency Center.

“It was a matter of understanding how things worked, putting a board together, getting by-laws in place, getting the 501c3, making sure the board was meeting on a routine basis, dealing with strategic planning, all those things that go into making the backbone of the Resiliency Center operate and stay in business, rather than the day-to-day,” he explains.

Buchanan and Cinque, the center’s executive director, have also helped it partner with other organizations from the beginning. The center formed an agreement with Tuesday’s Children, a group of 9/11 survivors who could partner with and help shape the center. Cinque’s conversations with survivors from the Columbine high school massacre and the Aurora theater shooting were also instrumental in designing it as a place anyone in the community could come to process trauma. The Resiliency Center has also worked with organizations related to successive mass tragedies like the Boston Marathon bombing, the Parkland shooting, and the church shooting in Charleston.

But Buchanan notes there is still much to do in Newtown, even more than six years later.

“You don’t just get over it, and it doesn’t just go away in a year or two,” he says, providing examples of people who have just recently come to the center for treatment, finally ready to cope with the trauma. Others are just now experiencing trauma triggers, even years later, or are jolted by news of similar shootings like the one at Parkland. Many of the children, too, are now at a point where they need to reprocess the event as they enter adolescence.

“The children we helped when they were six and seven years old, now they’re 12, 13 and 14 years old. Now you have to help them reprocess because now they’re adolescents. The brain is changing, their life is changing,” he says. “That may happen again when they go to college or something. There’s an ongoing need to help people process the trauma and go through it.”

With such a long-term mission, there seems to be inherent risk of burnout. But Buchanan says motivation remains high.

“You realize you’re making an impact—a big time impact—because it’s a small town. You see the people. You know the people. And you get the feedback directly,” he says. And, he adds, when the going gets tough, he remembers the 20 children who died that day in 2012.