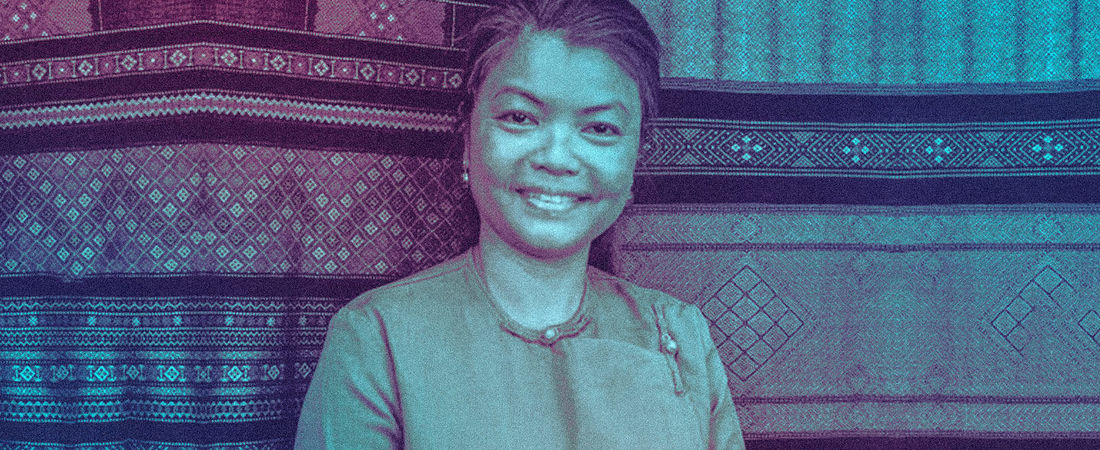

When she began exploring the history of her people, Mai Ni Ni Aung ’03 M.A. discovered one of their cherished cultural traditions was about to become a lost art.

The Chin people in Myanmar’s Rakhine State had long created highly intricate hand-woven clothing. But these beautiful items were vanishing.

The culprit, it turned out, was poverty. Many Chin, who struggled to afford life’s necessities, were selling older traditional garments to collectors and then buying cheaper, mass-produced clothes for themselves.

As she realized how bad things had gotten, Mai Ni Ni, who is Chin herself, had an epiphany: poverty might be threatening culture, but perhaps culture could provide a way out of poverty. She gathered great-aunts and other relatives and learned as much as she could about traditional weaving techniques. And then she began training other women and selling the textiles they produced.

That was 16 years ago, before Mai Ni Ni Aung came to Notre Dame, where she earned a master’s degree in peace studies through the Kroc Institute and honed her entrepreneurial skills during her award-winning performance in the McCloskey Business Plan Competition. Her effort has grown into Sone-Tu Chin Weavings, a sustainable social enterprise that now employs almost 300 women who have learned life-changing professional skills that enable them to help provide for their families.

“We are giving them life, hope, and purpose,” Mai Ni Ni says. “Once you have hope, everything else falls into place.”

It all starts with learning a craft. Chin weaving is highly complex, with more than 150 traditional patterns. The women who work for Sone-Tu learn to produce everything from clothing to household items such as tablecloths, napkins, and bedspreads.

“The first important thing you want to teach them is to have self-confidence and to take pride,” Mai Ni Ni says. “That will keep you going. If you are not proud of what you are doing, you will stop. We want to make sure they develop that passion and are proud of their roots and take pride in what they are doing.”

Women come from their villages to train, each bringing a teacher—often a relative—who will help mentor them once they return home. They spend up to a month learning a series of patterns, and they participate in a competition that offers a cash prize. They even learn to manage their newfound earnings. But the real payoff comes when they return home with new skills that allow them to contribute to their families’ incomes.

“They help support their parents, and they spend their own money,” Mai Ni Ni says. “Their social status is higher in society. The community sees them differently. And once the women start bringing money home, what do you see? Power balance. Before, she always got beaten by the husband, but now the husband is taking care of the child or fetching water or pounding rice. The women start bringing the money, which supplements the family income, and the power balance changes.”

Even as it helps the Chin people, Sone-Tu has already begun to branch out in preserving other cultural traditions as well. It now has weavers who have revived sarsikyo, the sacred Buddhist art of weaving ribbons adorned with texts and images.

“I like to stress that we are not just doing cultural preservation work for the Chin people,” Mai Ni Ni says. “We are also doing other traditional art. Once we make sure our pieces have been documented and we are confident enough that we have saved everything, we move to another traditional art.”

She also sees the economic empowerment Sone-Tu provides as a peacebuilding tool. Myanmar has long struggled with conflict between ethnic groups, and Rakhine State has received widespread coverage over the past year because of the violence and conflict that have forced more than half a million Rohingya people to flee.

“It’s all connected,” Mai Ni Ni says. “When people lose hope, that’s when they engage in these full-blown violence and atrocities. But when people have a future, they have hope, and they have more to lose than those who don’t. That helps prevent them from engaging in violence.”

In addition to empowering women and helping build peace, Sone-Tu helps fund a hostel that feeds, houses, and educates students who come from Chin villages throughout Rakhine State. Mai Ni Ni draws strength from seeing what the social enterprise has done and looks forward to helping it continue to grow.

“You are creating economic opportunity and at the same time you are preserving your old culture,” she says. “This is the best job you could ever have. You have the satisfaction of knowing you are giving life and purpose to future generations and to the fellow members of your community.”

To learn more about Sone-Tu Chin Weavings, please visit its Facebook page.